By, Judy Dixon

When Louis Braille first began pressing dots into paper for later reading, he did it by hand. His tools were primitive but effective; he used a slate and stylus. The top of his braille slate was a simple piece of sheet metal bent downward at the ends with small rectangular openings. The bottom of his slate was a flat stick of wood with horizontal grooves. The exact size and placement of these elements varied somewhat as Louis’s ideas for the best way to produce braille evolved over time.

Over the next hundred years, the tools for writing braille by hand became more sophisticated. The top and bottom of the slate were joined by a machined hinge, the back was often made with a distinct impression for each dot, and, in the latter part of this period, various plastics were used to reduce cost and weight, and increase resiliency.

Nine-line, wall-mountable slate for writing short memos--includes magnetic stylus, a roll of paper, and a hook for hanging messages.

My first encounter with a braille slate and stylus was just before Christmas in first grade at the school for the blind in St. Augustine, Florida. Early on the afternoon before Christmas vacation, the teacher gave each of us a slate and stylus. Mine was blue. She showed us how to use it and we had a few minutes to practice.

I took my new treasure home with me when I left for Christmas. I proudly demonstrated my new skill to my two older brothers. They already knew how to read and write and I had been very concerned about how I was going to read and write like they did. To this day, I can remember my exhilaration, “Look, I can read too, and I can write too.” I don’t think it occurred to me that they couldn’t read what I wrote. I could, and that was what mattered.

Throughout my school years, I took notes with a slate. By high school, I had a few different ones but they didn’t vary much because there was nothing very unique available in the U.S. at the time.

Early on, I was aware of the slate’s limitations. When using a slate in school, I often wished for one that had a full page of cells, eliminating the necessity of repositioning the slate down the page after every four lines. I also imagined a slate that would let me write very small braille so I could fit more text on a page. And how about one that could write on both sides of the paper? I did not know that such slates existed.

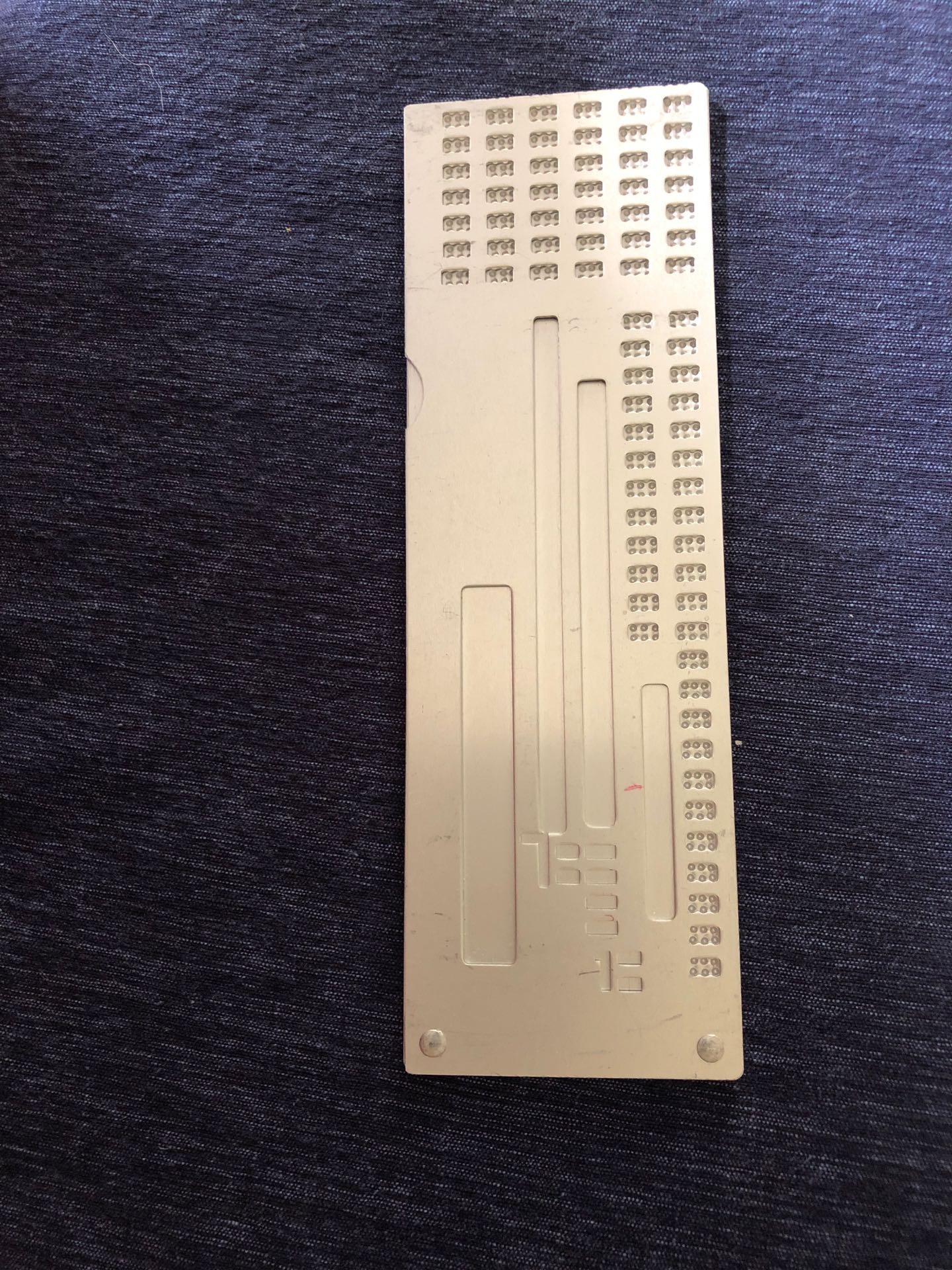

A four-cell slate to slip over a page edge for marginal notes.

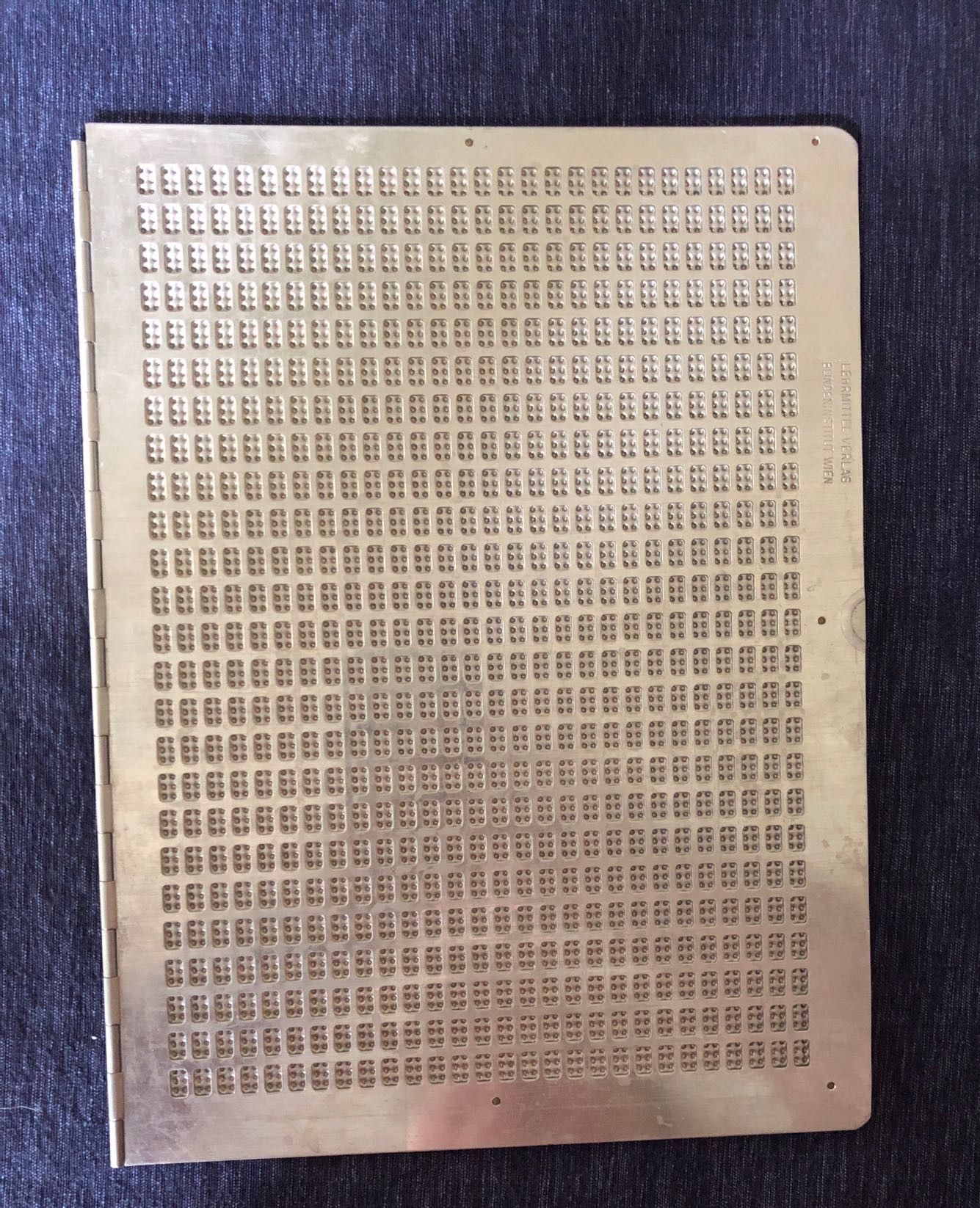

Some time in the 1970s, a friend gave me a slate from England. It had braille cells about two-thirds the size of the ones I had been using. On a 4-by-6-inch index card, I could fit 11 lines of 26 cells, far more than ever before. Later, on a visit to Germany, I got a full-page slate, 25 lines of 28 cells. It was made of a heavy metal and weighed about a pound but it was gorgeous. When I had a couple of dozen slates, I realized I was a collector. I was primarily interested in slates that had some function other than the ordinary ones.

Currently, there are 278 unique slates from 38 different countries in my collection. Some are historic, dating back to the 1860’s but most were made in the mid to late 20th century.

The vast majority are slates created to produce six-dot braille, but the collection also contains slates for tactile codes other than braille, such as New York Point, Moon Type, and codes created by individuals that were never widely used. It also contains slates for a German shorthand code, a Spanish music code, and a Japanese code for writing kanji—all extensions of the braille code using eight dots.

Element for IBM Selectric typewriter that produced very small but readable embossed braille.

The largest slate that I have was made in Austria and has 30 lines of 36 cells. The smallest, called a margin guide, was made in England and has only one line of four cells. It has no hinge and is designed to simply slip over the edge of a page like a paper clip. It is used to add a page number or make a note in the margin.

Full page metal slate from Austria

Each slate in my collection is somewhat different from every other. There are many different sizes and as many shapes. They are made of aluminum, zinc, brass, steel and several kinds of plastic--most of which are in fairly subdued shades of gray and black, but one is a startling fluorescent orange. Instead of pins, some have magnets or spring-loaded clips to secure the paper, and in place of a hinge, some have stiff tape or heavy plastic to hold the two parts of the slate together.

In the United States, we encounter only two sizes of braille, standard and jumbo. However, the size of the braille cell in slates from other countries varies considerably. The Japanese slates typically produce braille that is somewhat smaller than the American standard, while many of the German slates produce braille that is slightly larger than ours. There are two slates from Japan that produce braille so small that it is actually difficult to read.

Three cherry wood styluses produced in Japan to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the braille standard in the country.

There are several rather creative designs which allow the braille to be read while the paper is still in the slate. E-Z Read slates, which have pins in the top instead of the bottom, were common in the United States. But several models of slates made in Italy use magnets to hold the paper. As with E-Z Read slates, the braille can be read by lifting the back of the slate without disturbing the position of the paper. Magnets have an advantage over pins--they leave no holes in the paper.

Among my favorites are the slates that have been designed for special purposes. The Japanese have produced a telephone message slate which consists of a roll of paper, a small plastic slate, and a magnetic stylus, all mounted on a foam-backed board. Chemical Bank of New York developed an extremely useful checkwriting template. It has braille cells for making notes on the stub and on the check itself, as well as the familiar template openings for completing a check with a pen. This slate was provided to any blind person opening an account with Chemical Bank and was sold to any other bank requesting it for their blind patrons.

Aluminum check writing slate distributed by Chemical Bank of New York. Includes slots for filling out check with a pen and braille cells on the check stub and check itself for braille notations.

A few slates have their own associated stylus but there is a collection of several hundred styluses as well. Special ones include three cherry wood styluses made in Japan to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the braille code and an ivory stylus used by George Shearing, the blind jazz musician, that he used during his school days in the 1920s.

An ivory-handled stylus used by the blind jazz musician, George Shearing, at the school for the blind in England in the 1920s.

The collection is contained in two wooden cabinets that were specially made for it. Each one has 36 drawers, with pocket, board and notebook slates in Cabinet A and non-braille, upward-writing, special, and full-page slates in Cabinet B. It also has its own web site, www.brailleslates.org.

Although slate use has waned considerably in the developed world, writing braille with a slate and stylus is still widespread in developing countries.

The advantages of a braille slate are numerous. Slates are relatively inexpensive, very portable, quiet to use, require no batteries, and need little, if any, repair.

But writing with a braille slate can be very confining. Unlike using a pen or pencil, it is not possible to vary the size of the letters, to write between the lines, or to scribble in the margins as those who write print so often do. Maybe this will happen one day and maybe, ironically, it will be technology that does it!

Judy Dixon is the Consumer Relations Officer for the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. She has an extensive collection of both slates and braille notetakers. Judy writes many original technology books for NBP and serves as a judge for our Touch of Genius Prize for Innovation. All photos were taken by Judy.

This post was updated on October 22, 2019.