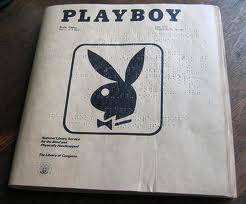

The first braille I ever laid eyes on was a braille Playboy belonging to my blind friend, Edgardo, who lived on the third floor of my apartment building. It had the word Playboy emblazoned in black ink across the front cover

with the iconic rabbit-in-a-bowtie logo and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped printed in the bottom left-hand corner. But when I opened the magazine up, it was completely blank—a vast expanse of white goose bumps, a blizzard of snowy dots.

I remember asking Edgardo, half jokingly, “Where are all the pictures?” and turning the magazine over and over in my hands, wondering if it was upside down or right side up. So many dots, each one casting a tiny shadow, like the view from an airplane flying over a country of igloos. “It doesn’t have any pictures,” said Edgardo, taking the magazine from my hands and reading it silently to himself. “But it has descriptions. And it has captions. And I have my imagination.”

Then he began to read aloud: “Becky Dupree, Miss March, leans seductively against a door jamb of the barn, wearing a cowboy hat and a button-down cerulean shirt open to her navel…” “Get out of here! It doesn’t say that,” I said. “Take a look at this,” he said, handing me back the magazine,his index finger-pointing to a row of dots halfway down the page, as indecipherable to me as a “You Are Here” sign in Mandarin. I was intrigued. So this was braille. But how on earth did it work? How were the letters represented? The punctuation? The paragraphs? Where was the alphabet in all this whiteout of dots?

It was right then and there that I resolved to learn it; to teach myself braille; to see for myself if Becky Dupree was indeed wearing a cerulean shirt unbuttoned to her navel. I was going to demystify this inscrutable code that most people, myself included, assumed was something that only the blind could apprehend. What did I have to lose?

It was right then and there that I resolved to learn it; to teach myself braille; to see for myself if Becky Dupree was indeed wearing a cerulean shirt unbuttoned to her navel. I was going to demystify this inscrutable code that most people, myself included, assumed was something that only the blind could apprehend. What did I have to lose?

Braille was the most interesting, the most provocative thing to cross my path since I’d broken up with my college girlfriend and run away to Boston where I was working a dead-end job in a delicatessen. With nothing to claim my interest or attentions, why not give myself over to braille?

“May I keep this?” I asked Edgardo, holding the braille Playboy to my chest in a protective, possessive attitude, as though it were Becky Dupree herself. Luckily, Edgardo was willing to part with the magazine, seeing as it was the March issue and we were now in the middle of July. He was months behind in his reading, the braille Playboys, Reader’s Digests, National Geographics and Washington Post Book Worlds in piles all around his apartment, leaning towers of braille growing precariously toward the ceiling like stalagmites in a dark cave.

The day after commandeering Edgardo’s Playboy, I signed up for a correspondence course in braille transcription through the Hadley School for the Blind in Winnetka, Illinois, and I spent the next twelve months learning the braille code. I kept Edgardo’s Playboy under my bed for that whole year, taking it out and dusting it off now and then to hunt for Becky Dupree, who, when I was finally fluent enough to find her, wasn’t even in there in the end. Once I’d read the whole issue, front to back, I finally realized, a little too late, that Edgardo had invented her. He’d made her up just to get my goat, which in the end is what goaded me on to learn braille.